Firestone

Click here for further readingBuilt in 1928, the Firestone Factory was the first overseas factory opened by the American Firestone Tire & Rubber Company Ltd. Favourable Government import duty on tyres made it more cost effective to manufacture in the UK.

Firestone was the second factory to open on the Great West Road, also known as the ‘Golden Mile.’ The Firestone Factory was designed by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners, architects with a specialism in reinforced concrete construction and who were seen as the leading designers of industrial buildings.. The Hoover Building in Perivale and Victoria Coach Station are other examples of their work.

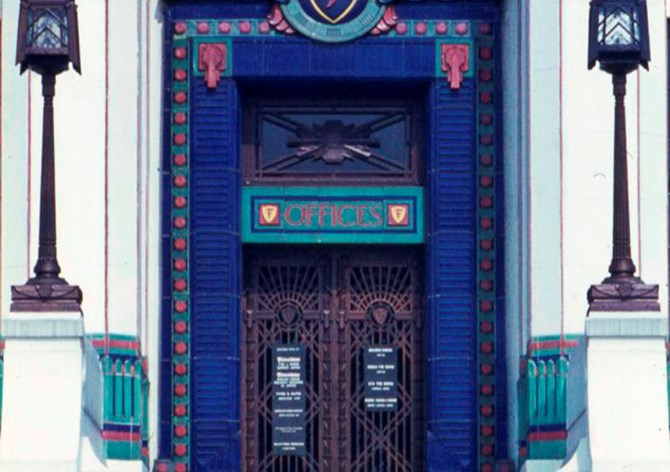

The Art Deco style of the building was at the time called jazz modern (or moderne) recognisable by the use of simplified classical forms decorated with “jazz age” motifs. In other projects Wallis, Gilbert and Partners had started to incorporate ‘Egyptian’ details in their designs and the Firestone factory design was inspired by an Ancient Egyptian temple.

The building was designed in three weeks and built in 18 weeks. It was on a 27-acre site set back from the road with a lawn at the front and a decorative façade. The administration building at the front was two storey, reinforced concrete with a white cement and decorative tile finish. Behind that, a four-storey building housed stores, repair shops and other facilities, while the factory floor itself was single storey.

“A good and pleasing design is an efficient advertising medium; moreover, a well-designed façade has a mental effect on the employee in whom it creates respect, and the feeling of an agreeable environment thence arising reacts favourably upon his output.”

Paul Lucas, former employee, on the building

Audio transcript

A: The middle side was the posh area where you had these wonderful bronze gates and huge lanterns and a marble staircase which I don’t think I ever managed to go up and that led straight into the Directors’ suite.

Q: So that was from reception?

A: Yes, from reception. Well, posh reception was down there! The centre building was the same design exactly as the Akron number one building in Ohio and that was worth saving because it was neo-Egyptian, a bit like the Hoover building in Perivale. Either side it was slab concrete painted white with all Crittall windows, you know the metal windows. When they wanted to paint the building because it was getting a bit dilapidated, they painted everything they could see from the road or from the railway. Everything else was left coated in whatever black it was. It was quite impressive. You had this nice sloping grass in front of the building and occasionally, at least on two occasions, the Army came by with their horses and rested them there on the way to London.

Q: On the grass outside?

A: On the grass outside. Only a couple of occasions I think that was.

Q: How did you feel about it being knocked down?

A: Oh, very sad. They could have at least kept the centre bit, which is the bit they hit first. I mean the rest of it was pretty nondescript but the centre bit was to my mind worth preserving.

Inside the Firestone Factory

Working conditions

Firestone had a canteen, shower facilities, a hospital room, drinking fountains and a sports ground. At its opening it was heralded as an exemplar of what could be achieved for employees' wellbeing. Social clubs attached to the factory were very common and popular with staff.

However, working conditions were far from ideal. While the exterior of the factory was attractive, life on the shop floor was reportedly very unpleasant; hot, dirty and, inevitably, with a strong smell of rubber.

Paul Lucas, former employee, on the working conditions

Audio transcript

In the offices, being as anywhere up to I don’t know how many people, but rows and rows of people, it could get a bit stuffy I suppose. And people smoked. The other thing was the carbon black, which was one of the main constituents of tyres, used to seep out from the factory and so when I got home my shirts were black round the collar from that. Generally the conditions were quite good but across the front of the building, in front of these rows and rows and rows of desks, there were the offices facing out onto the front and they were the managers and main finance people etc.

Peggy Farmer, former employee, on social clubs

Audio transcript

Yeah they did, they had a nice sports club. We used to go up there on a Sunday. I used to go to dances up there as well at Firestone. A lot of the men used to go and play snooker up there you know. But I used to go up. It was a nice social club up there; it was a big one as well you know, it was OK. I didn’t get too involved in it, now and again. But I know the men used to go up and play snooker on a Sunday evening. I’m talking about my family; they used to go up there on a Sunday and you could always, like one of my brothers didn’t work there but he always went with the other brother to go and play snooker. So they used to let outsiders come in although you wasn’t a Firestone member.

Inside the Firestone Factory

Factory closure

The Firestone Factory celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1978 and published a brochure which was very upbeat about the future. However by early 1979, 55 workers had been made redundant when the remould operations were shut down. The introduction of the tubeless tyre meant less demand for inner tubes. By November it was clear that the factory would close due to continuing losses and a decline in the market for Crossply tyres.

Firestone workers vowed to ‘go down fighting.’ The factory union, the TGWU, and the management looked into various options to make the plant viable but despite their efforts the factory closed on 15 February 1980. Half the workforce was from the Brentford and Chiswick areas, with many working for the company for more than 20 years. Most of the 1,500 workforce found new jobs, many with London Transport (now TFL) and Ford.

Interest in acquiring the site came from the automotive and electronic sectors. Hounslow Council was keen to ensure that the site remained industrial, partly to keep unemployment figures low.

The factory was offered for sale by agents Garrard Smith at £22 million, making it the largest single industrial property sale in Britain (were that price to be achieved), and the largest area of land sold in London for many years. In March 1980 it was reported that a number of companies were discussing plans for the site with Hounslow Council; some wanting to occupy the buildings, others with redevelopment or refurbishment plans.

The site was sold to Builders Amalgamated, a subsidiary of Trafalgar House Group.

“Architecturally, Firestone’s building is a classically extravagant 1920s design. A grand flight of stairs leads from the road through the lawn in front of the buildings to a huge front door beneath the clock in the centre of the symmetrical building. The steps rise between intricately detailed white walls bearing art-deco lamps. The front door is behind two equally period metal grills – all set in a huge surround in blue, orange and green… Some, no doubt, find the buildings hideous, though others regard them as an architectural gem. They are not listed, however. Demolition of the frontage is by no means certain though”

Peggy Farmer, former employee, on the factory closure

Audio transcript

A: I did hear, and we didn’t believe it, it was unbelievable it really was. Two of my brothers got made redundant from Firestones. I’m afraid they’ve both passed away now. But they were gutted. My husband worked at Firestones and he got out before, he left before it was closed down but they did hear it was on the cards that they were going to move or move out of the area. My two brothers were absolutely shocked. I think – Brasher that man’s name was, Brasher, John Brasher, I’m sure that’s what his name was – he called a, this is what I’ve been told by my family, he called a meeting and said that it was being closed down. And it was quick, it was quick. One minute they were there, the next minute they were gone.

Q: So, why were they shocked about the closure?

A: I don’t know. They just always thought it was going to be there. It was always going to be a job that they…they said that they thought it would be there forever, you know what I mean? It was like all the factories down the Great West Road like Trico for instance; you never thought they were going to go. They were always going to be on the Great West Road, because it was called the Golden Mile you know.

Inside the Firestone Factory

Listing and demolition

The Thirties Society (later renamed the 20th Century Society) originally wrote to the Department of the Environment on 17 July 1980 warning that there was a danger the building would be demolished.

During the week of 18 August 1980, an inspector from the Department of the Environment visited the Firestone Factory and decided to ‘spot list’ it as a building of architectural and historical importance – an emergency procedure to protect it from demolition. But the factory was by now in the process of being sold to the Trafalgar House Company and contracts were exchanged on Friday 22 August.

Hounslow Council received an anonymous tip off on the afternoon of Friday 22 August that the new owners were planning demolition. They held eleventh hour discussions with the Department of the Environment about implementing the spot listing until a decision could be taken on the building’s architectural value. By the time a Department of the Environment photographer arrived to start the process, it was too dark for him to take photos and, being a Bank Holiday weekend, nobody was available to sign off the emergency spot listing. Hounslow Council’s Deputy Planning Officer was told that the listing couldn’t become effective until the following week.

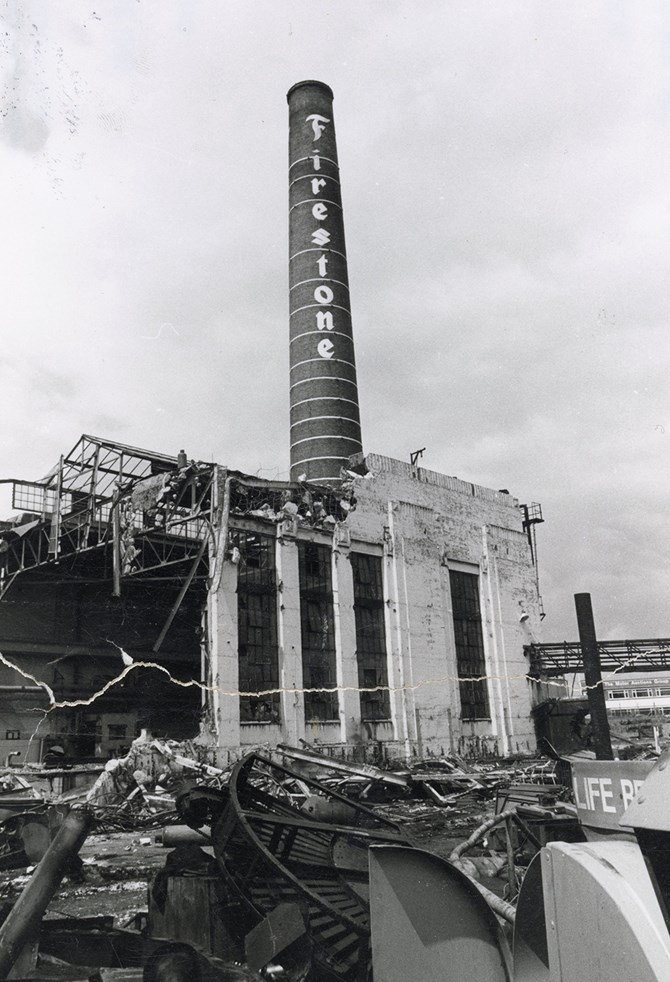

The new owners took advantage of this delay by sending in demolition gangs on Saturday 23 August. Most of the building was reduced to rubble within a day.

300 administrative staff were still working at the site prior to the demolition. The plan had been to remove them within the next two years – they had no indication that their offices were about to be demolished.

Ernest Barlett, former employee, on the demolition

Audio transcript

As she [Ernest's daughter] came along the Great West Road, the building, she noticed the building had several cranes working on the main offices with large iron balls. This could only mean one thing, they were knocking it down. So not wishing to miss anything we [decided we] will have a look on the way out, which turned out to be nearly all day.

I said to my daughter how nice it would be if we could have one of the ceramic tiles with a Firestone emblem, that was part of the very attractive main entrance. And then [she] called over the railings to the owner of the site, sorry, I’ve forgotten the name and his title, that her dad had spent so many years in the engineering department, and could he have one of the emblems as a souvenir? To my surprise he called over what was obviously the contractor foreman who stopped the job to see if he could get the emblem but unfortunately the man reported that, having checked, [he had] found that to remove it was impossible without breaking it. But he did bring a plain tile which I have to this day.

“I can recall few buildings of the last decade whose destruction has produced more spontaneous outrage from laymen…. It is a marvellous building, and this was a monstrous piece of vandalism. There was a serious demonstration of incompetence in not getting this building listed in time, and what remains of the wings and environs must be spot listed now. ”

Inside the Firestone Factory

The Aftermath

The demolition angered local residents and the wider public.

Marcus Binney, chairman of the pressure group SAVE Britain’s Heritage, backed by the Thirties Society and the Ancient Monuments Society, wrote immediately to Michael Heseltine (then Secretary of State for the Environment) to propose listing what remained of the building after demolition. SAVE Britain’s Heritage also wrote to Hounslow Council asking them to put an enforcement notice on Trafalgar House Company ordering them to restore the building. But in Hounslow’s view the demolition had not been illegal so they felt they had no power to do so.

The Department of the Environment officials “expressed surprise” at the disappearance of the factory over the Bank Holiday.

Trafalgar House meanwhile denied that the demolition was rushed through so development was not delayed and the company could get a quick return on its investment. However, Lord Matthews of Trafalgar House said “Sometimes, something that’s attractive does not make money. We looked at the scheme which maximised development, and that did not allow for it to stay.” Within Hounslow Council there were mixed feelings about the demolition: Alfred King, leader of the Council, said “I don’t see this building as having been a thing of beauty and new employment in the area is urgently needed.”

The Firestone Factory’s remaining gates, railings and lanterns were listed by English Heritage (now Historic England) in October 2001. The demolition of the Firestone Factory focussed attention on the need to preserve 20th century architecture and led directly to a large number of buildings, such as Battersea Power Station and the Hoover Building in Perivale, being given listed status