“[On the closure of the factory] Walking through the factory was like walking through a mausoleum, you know, I mean no noise, nothing, and you could see the people were sad about going on, losing our friends, losing our comrades, moving on.”

Mick Martin, former employee, on working conditions

Audio transcript

Of course, you can imagine, it was a big automobile factory and there was a lot of dust around. There was no cloakrooms. What you had to do was when you went in, in the morning, when you took off your coat and whatever you were taking off, they used to lower a big hood from the ceiling and people used to hang their coats up. And when they’d all done that, they pulled this thing up to the ceiling - of course, not knowing that that was where all the oil and all the dust used to go, up into the ceiling. So the coats didn’t last very long, I can tell you, without having to be cleaned!

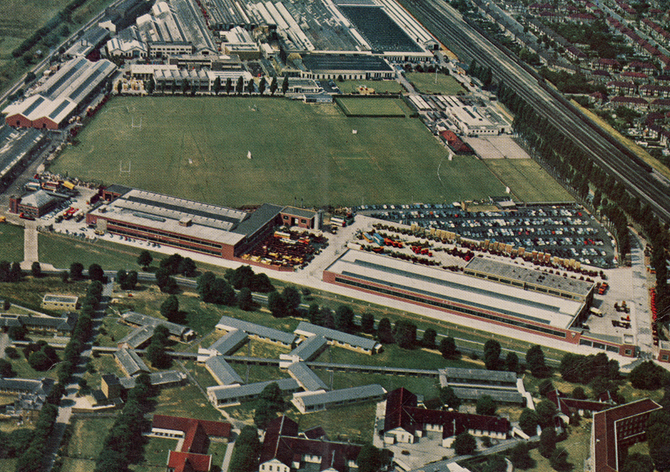

Inside the AEC Factory

A typical day

A shift on the factory floor at AEC Southall would start at 8am. Pay was average for the area and regulated by the Employers’ Federation. Initially it comprised an hourly rate plus a piece rate (dependant on the amount of work done) but later the piecework rate was dropped. Another improvement was the introduction of holiday pay. In the 1960s there was no pension scheme so the Union Shop Stewards introduced their own scheme.

Most shop floor workers were engineers who would have needed prior education and experience or else would have been trained up through a seven-year apprenticeship scheme. Employees would often have social gatherings, summer fairs and Christmas parties. They would receive awards to celebrate and honour those who were employed for 10, 25 and 50 years. AEC jobs were seen as secure and for life.

In the 1950s, Southall became home to many new Afro-Caribbean and South Asian migrants. Although the numbers of migrants in the local area increased in the 1960s, this demographic shift was not reflected in staffing at AEC Southall. This was for several reasons, one of which was that the engineering jobs required qualifications which new migrants often did not have, another was that they would need to apply through the apprenticeship scheme. From oral histories we understand that there was a low level of acceptance of applicant apprentices from migrant communitie

There were anti-immigrant sentiments amongst some floor workers. For example, a group of employees walked out to show support of Enoch Powell's Rivers of Blood speech in 1968. The Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) Archives held at the Modern Record Centre at Warwick University record the firing of Brother S, a South Asian worker after white workers refused to work alongside him. The AEU disagreed with the management’s decision to fire Brother S and was able to ensure AEC offered him a role at the Watford factory. Brother S decided not to take the job and found different employment still within the area.

Towards the closure of the factory, we see through images of the apprenticeship evenings in 1979 that there were a high number of South Asian apprentices, demonstrating a shift in management's attitudes.

Mick Martin, former employee, on Afro-Caribbean workers overturning the colour/race bar

Audio transcript

When I went there we had some African Caribbean men there, right, but none of them worked on the machines, they were all labourers, labouring, the labourers, none of them were given jobs on the machines. And some of us became very concerned about that, certainly I did because when I went there I couldn’t believe it. I mean if you went on the weekend when they were cleaning out the spray booth you certainly wouldn’t think you were in England, you’d think you were in a Caribbean country because every one of the people would be Black and I mean they… but some of us got together, and we worked together and of course we worked together, and then eventually we persuaded the company that it was in their best interests to start off these lads with jobs, because some of these lads were skilled but because of the nature of the employment they wouldn’t have been offered the jobs. But anyway, we got that fixed, we got that fixed.

Inside the AEC Factory

Changes in Management

In 1962, AEC merged with British Leyland Motor Corporation Ltd (BLMC). The merger combined most of the remaining independent British car manufacturing companies, including over 100 different companies. BLMC was thrown into turmoil with mismanagement in production, industrial relation problems with trade unions, the 1973 oil crisis, the three-day week, and high inflation.

The workers of AEC Southall mobilised strikes and occupations against the cutting of shifts and redundancies. In 1975, the Government became a major shareholder to rationalise and to try to save the company. 700 workers at AEC Southall took voluntary redundancy as lorry production was phased out. In early 1976 the company would scale back to only produce engines, reducing the workforce from 4000 to 2500. Syd Bidwell, the local MP, argued for the modernisation of the factory so it could continue to be used.

In March 1977 fresh hope came in the form of the announcement of a confirmed plan for a new London Transport Bus to be produced at AEC Southall. By October 1978, the plan was reversed. Instead, it was declared that production would be sent to the Park Royal factory. The following month British Leyland announced that the AEC Southall plant would be closed. 19 May 1979 was the last day for 2000 workers with 300 remaining to clear the factory. A job centre was set up on site and many engineers went to work at London Transport, repairing the buses they had previously been building. In the 1980s Southall had an unemployment rate of 10% whereas across the rest of outer London the average rate was 3.86%.

Mick Martin, former employee, on the decision to close the factory

Audio transcript

When they decided to close AEC, I mean, there’s no mistake [mystery?] that there was a big meeting in Lancashire which I attended, and it became obvious that the north-western MPs and the Labour Party were plugging to have the big factory built up in Lancashire. And of course, they built the new plant there, the new track and all the rest of it. And, of course AEC then was becoming surplus to their requirements. They wanted, they put axles into AEC but nothing ever came of it and I mean at the end of the day what it was, was the pressure from the MPs in the Northwest on Leylands and of course the fact that Leylands was a nationalised industry. It was a nationalised industry. So that’s what happened to AEC, that’s how we managed to close down and the rest of it.